China’s gloomy demographic outlook will loom large over Beijing policymakers in the years and decades to come. Data released by the National Bureau of Statistics in early 2022 reveal the depth of the challenge, showing a sharp slowdown in population growth and a quickly greying workforce.

In 2021, China’s population reached approximately 1.412 billion, up by 480,000 people from the year before. That is a natural population growth of just 0.034 per cent – the lowest rate recorded since the founding of the People’s Republic.

The sharp slowdown does not come out of nowhere. Rather, it is the result of a plummeting fertility rate and a quickly ageing society:

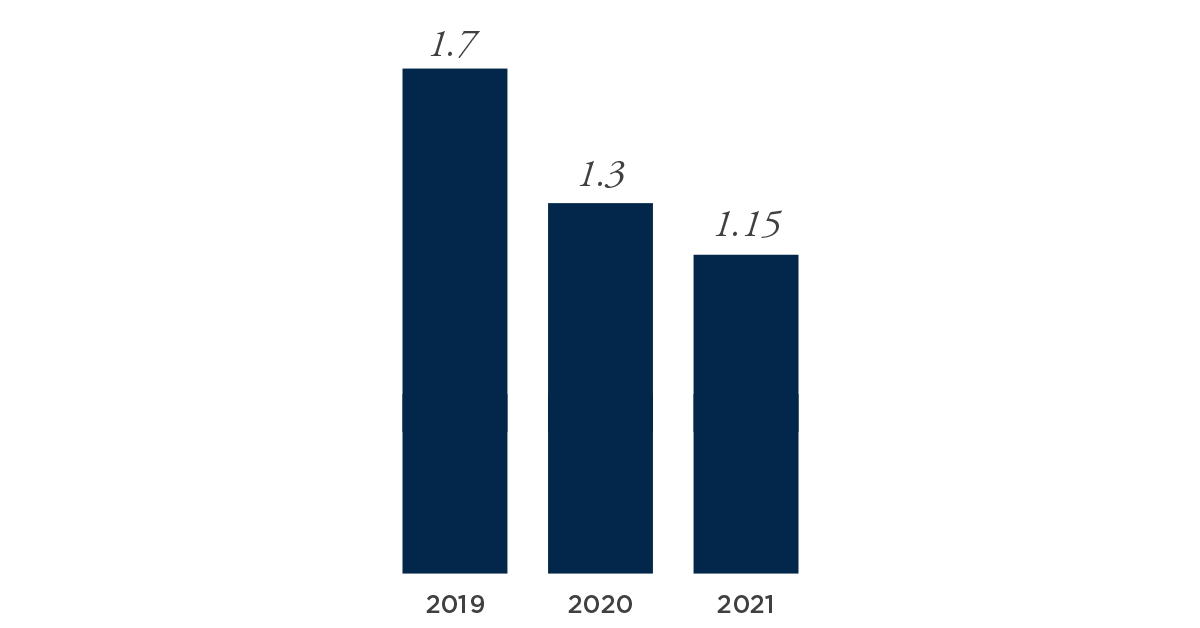

- Fewer babies are born. Following a slight uptick in 2016 due to the easing of the one-child policy, births in China have fallen steadily in the five years since. In 2021, only 10.62 million babies were born – an 11.5 per cent drop from the 12 million in 2020. This puts China’s total fertility rate at 1.15 children per woman (a record low), far below the 2.1 replacement level.

- The number of seniors is rising. In 2021, the proportion of the population over 65 years old was 14.2 per cent – up from 9.1 per cent in 2011.

Fertility rate (children born/woman)

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

In addition, demographers warn that China’s massive urbanisation push will put additional downward pressure on the already dwindling birth numbers, as city dwellers tend to have fewer children than their rural counterparts. According to UN projections, China’s urbanisation rate will hit 80 per cent in 2050 – up significantly from 64.7 per cent in 2021. Most of the new city dwellers are expected to move into lower-tier cities.

Taken together, these trends will have large implications on China’s workforce structure. Growth in China’s workforce peaked around 2014; but as these trends are set to continue the currently one billion strong working-age population is projected to plummet by more than 130 million by 2040. By mid-century, the share of the working-age population is projected to fall to 50 per cent.

This shift will have serious implications on China's continued economic prospects, as the country’s huge population and its many young workers have been a large part of its strong economic growth over the past decades. To make matters worse, these trends will also put significant downward pressures on China’s already strained retirement system – further depressing growth prospects.

THE GOVERNMENT WANTS CHINESE FAMILIES TO MAKE MORE BABIES

To stop the quick demographic decline, and replenish the workforce, Beijing has passed several policies to make it more attractive for Chinese families to have more children. These include dropping the one-child policy – often attributed for the depressing demographic outlook – allowing couples to have a second child in 2016, and then a third in 2021. As noted above, these measures have so far had limited effect.

Beijing has also rolled out several policies aimed at reducing the financial burden of raising children. These include a central ban on for-profit after-school tuition in 2021 (which completely tanked the country’s booming edtech sector) as well as regional government incentives, including offering childcare subsidies and extended parental leave.

To minimise the pressure on the state retirement system, the government has also started the process of raising the retirement age. At its current levels, 60 for men, 55 for female blue-collar women, and 50 for white-collar women, it is among the worlds’ lowest. As expected, this has been met with quite a significant public backlash. And in the 14th Five-Year Plan issued in March 2021, the government said that the retirement age would be raised “gradually” over the next couple of years.

Percentage of population over 65

Source: China Development Research Foundation

THE ONE CHILD FAMILY STRUCTURE LOOKS LIKE IT IS HERE TO STAY

Despite the government’s best efforts, the easing of family planning policies has so far been insufficient in reversing the slowdown in baby making. That is because, unsurprisingly, government incentives are not the only thing affecting people’s interest in having children. More women in the workplace, changing attitudes towards marriage, the rising cost of living, a hectic 996 work culture* , and changing expectations towards quality of life have all affected (young) people’s willingness to have children. Over the past three years, these trends have been exaggerated further by economic uncertainties brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is worth noting that these trends are not unique to China but can be seen in most developed or newly industrialised countries – including Sweden. But whereas European countries grappling with dropping fertility rates have managed to stabilise the population by immigration, China is unlikely to use this method to solve its demographic woes.

China’s democratic shift offer both challenges and opportunities for Swedish companies

It is worth noting that these trends are not unique to China but can be seen in most developed or newly industrialised countries – including Sweden. But whereas European countries grappling with dropping fertility rates have managed to stabilise the population by immigration, China is unlikely to use this method to solve its demographic woes.

A shrinking workforce

The shrinking workforce will be a big challenge for China’s industrial and manufacturing sector. The increasingly limited labour supply will put upward pressure on salaries and increase the cost for Swedish companies with production on the ground in China. This shortage will be especially pronounced in factories as workers pursue higher paying jobs in the services industry (e.g. in the delivery sector).

According to our Business Climate Survey, talent attraction has been flagged as the number one challenge for Swedish companies in China for the past two years. Companies should prepare for such challenges to continue, and get more pronounced, in the short to medium-term.

On the flip side, this shift will speed up the automation process of Chinese factories, giving impetus to a boom in robotics and the industrial internet industries. The rising automation of the industry will require more educated workers. Investment in education on a national scale will therefore play a vital role in driving productivity – offering opportunities for companies in the education sector, especially for those in adult education and training. This will also bring opportunities for companies providing solutions that reduce the need for workers, including those that help improve productivity, automation, etc.

New consumer groups

As China’s demographic structure changes, with seniors constituting a larger part of the population, more young people give traditional family life a pass, and more people living in lower-tier cities will give rise to new consumer groups.

As the silver economy expands, there will be great business opportunities in the healthcare and elderly services market, as well as in consumer products tailored for an older audience such as smartphones with big buttons, at-home care services, mobile healthcare solutions, etc.

Due to the demographic shift, singles and DINKs (double income, no kids) are growing consumer groups in China. Singles have niche preferences and tailored consumer products, such as small/single sized products, have proven extremely popular in China to date. This offers ample opportunities for Swedish consumer brands to create new products specifically targeting this demographic. Meanwhile, DINKs tend to have more cash on hand to spend on luxury goods and to use for leisure travel, as compared to their “child-burdened” peers, so Swedish companies in these sectors should benefit as well.

Swedish companies should also be aware of the opportunities presented by China’s increasing urbanisation, especially the influx of people to lower-tier cities. While often misunderstood as rural, conservative spenders looking for low-priced goods, these consumers are increasingly wealthy and are more and more willing to spend money on premium brands and novel travel experiences. Understanding how to reach this clientele will be key to continued success in the Chinese market for Swedish consumer companies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Swedish companies should be well positioned to leverage new and existing products and solutions to take advantage of the massive demographic shift underway in China today. Meanwhile, companies should prepare for struggles to attract talented personnel, a key headache already, which is likely to increase in coming years as competition for highly skilled individuals intensify.

Swedish companies should also keep in mind that while these challenges might be a small headache for companies, they are a massive migraine for China’s macro planners. Solutions brought by foreign companies to help policymakers meet these challenges will be met by open arms by the Chinese government and should facilitate for market entry / market access / bigger sales down the line.

*The 996 work culture is the practice of working 9am to 9pm, six days per week and is a common practice amongst Chinese tech companies and startups. Though mandatory 996 schedules were banned by Chinese courts in August 2021, the practice is still enforced informally by many companies.